By using the legend of Keibu Keioiba—a half-man, half-tiger figure—the play delves into the duality of human nature, mirroring the turmoil of a fractured society.

By Usham Rojio

The students of the School of Drama and Fine Arts at the University of Calicut in Thrissur, Kerala, showcased remarkable determination in bringing their production of Keibu Keioiba (Tiger-man) directed by Heisnam Tomba to Imphal on January 19, 2025, the third and final day of Celebrating Heisnam Kanhailal 2025. Overcoming significant challenges, they successfully funded their journey through crowdfunding initiatives and received crucial financial support from Manipur’s theatre fraternity as well. Their performance was a part of the celebrations marking the 84th birth anniversary of the renowned theatre director Heisnam Kanhailal and the 50th anniversary of his iconic play Pebet held from January 17 to 19 at the Chandrakirti Auditorium in Palace Compound, Imphal.

This collaborative effort underscores the solidarity within the Indian theatre fraternity and highlights the students’ commitment to cultural exchange and artistic expression. Their journey and performance not only enriched the commemorative events in Imphal but also served as a testament to the unifying power of the arts across diverse regions.

Heisnam Tomba’s play Keibu Keioiba, which was recently staged in Imphal, was premiered at the School of Drama and Fine Arts, Thrissur in November 2024 as a part of the one-month worshop-cum-production course. The play reimagines the Manipuri folktale as a powerful allegory for contemporary violence and political strife in Manipur. Departing from traditional storytelling methods, the play relies on minimal dialogue, placing greater emphasis on movement, expression, and action to communicate its themes.

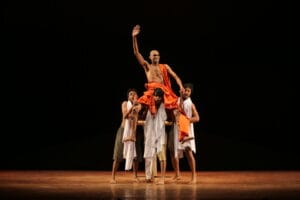

By using the legend of Keibu Keioiba—a half-man, half-tiger figure—the play delves into the duality of human nature, mirroring the turmoil of a fractured society. Tomba’s direction prioritizes physical theatre, where the actors’ bodies become the primary medium of narration. The performers, students from the School of Drama and Fine Arts, bring raw intensity to their roles, evoking testimonies of suffering through evocative gestures, dynamic choreography, and symbolic imagery.

The production design is equally striking, with lighting and sound (designed by the students themselves) playing crucial roles in creating an immersive experience. Tamba uses traditional Manipuri performance elements, such as indigenous rhythms and stylized movement, that enhance the play’s emotional depth. The absence of conventional dialogue forces the audience to engage with the story on a visceral level, making the experience more poignant and unsettling.

By contextualizing Keibu Keioiba within the current socio-political climate of Manipur, Tomba transforms folklore into a sharp political critique. The play becomes a reflection on violence, displacement, and the struggle for identity in a land suffered with divisive politics for political gain. Its unconventional approach challenges conventional theatre norms, proving that silence and physicality can be just as, if not more, powerful than words. The play unfolds in a manner that transcends regional boundaries, making it a deeply universal experience.

From the very beginning, Tomba’s direction breaks cultural barriers. Just ten minutes in, an old Malayalam farming song plays. The rhythm of sowing and reaping becomes a shared metaphor, binding the spectators to the onstage world. The early moments of the play depict everyday life—farmers tending fields, artisans weaving bamboo sieves, potters shaping clay—painting a serene picture of rural existence, not just in Manipur but across India.

But this tranquility is short-lived. The sudden arrival of army men shatters the peace. Their orders—‘kill anyone suspicious’ and ‘everyone in sight’—echo a brutal reality. Innocence is massacred as soldiers murder sleeping women under the symbolic protection of two towering figures of Indian history—Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi. This imagery is deeply unsettling, questioning the very ideals of justice and non-violence that these leaders stood for.

Tomba’s minimal-dialogue approach heightens the play’s impact. The actors rely on movement and expression, making the violence more visceral. The soundscape—traditional Manipuri rhythms mixed with silence and sudden gunfire—creates a haunting atmosphere. The juxtaposition of folk traditions with raw brutality forces the audience to confront uncomfortable truths about power, oppression, and the cost of conflict.

Keibu Keioiba is not just theatre—it is testimony. It challenges, provokes, and refuses to let its audience remain passive. By fusing folklore with contemporary socio-political realities, Tomba crafts a performance that is as much a lament as it is a call for awareness. The play leaves behind an echo—one that lingers, demanding reflection long after the final scene fades. The play poignantly captures the agony of a people trapped between conflict and forced survival, using a mix of realism, mythology, and powerful visual storytelling.

The depiction of traumatised villagers being pushed into relief camps is one of the most striking moments of the performance. Stripped of agency, they are forced to navigate a system that reduces them to economic irrelevance, compelling them to sell useless goods—symbols of a capitalism that does not account for their existence. This imagery reflects the helplessness of communities displaced by conflict, highlighting how systemic oppression functions not only through violence but through economic alienation.

The irony deepens when a Hindi-speaking ‘national politician’ arrives, preaching peace. Instead of engaging, the villagers hide—a quiet but powerful act of defiance. Their retreat signifies a loss of faith in external governance, emphasizing how the state’s interventions often fail to resonate with those on the margins. The choice of language—Hindi—further underlines the disconnection between centralized authority and the diverse realities of India’s regions.

Pantoibi and Thabaton, goddesses of the land, witness the villagers’ suffering, appearing as silent yet compassionate figures. Their presence reinforces the deep spiritual and cultural wounds inflicted upon the land and its people. But despite their attempts to intervene, even divine forces seem powerless against the machinery of oppression.

The image of the three musketeers chasing Thabaton serves as a potent metaphor for the vulnerability of women in conflict zones, reflecting how their bodies often become the battlegrounds of male aggression and competition. The musketeers’ rivalry over ownership of Thabaton, culminating in their fatal conflict, underscores the destructive nature of patriarchal dynamics and the absurdity of violence.

The transformation of the deceased musketeers into children holding lollipops poignantly illustrates the futility of gun culture. This shift from weapons to childhood innocence symbolizes a yearning for peace and the tragic loss of potential lives to violence. It contrasts the harsh realities of conflict with the innocence and simplicity often overlooked in such dire circumstances.

The introduction of the Sadhu Baba and the playful renaming of the musketeers as LOL, LI, and POP adds a layer of political satire. The humorous rendition of the song about lollipops further emphasizes this satire, cleverly weaving fun and irony into serious commentary. By employing a lighthearted tune to address heavy themes, the play disarms the audience and prompts them to reflect on the absurdities of war and the societal implications of gun culture in contemporary Manipur.

Overall, this blend of humor and tragedy not only provides comic relief but also engages the audience in critical reflection on the ongoing socio-political issues in their environment, urging them to reconsider their perspectives on violence, conflict, and the protection of vulnerable individuals in society.

The play’s final image lingers long after the performance ends. The Sadhu Baba, an army chief, and a politician enact the infamous ‘see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil’ gesture—a damning critique of institutionalized denial. In the foreground, a little girl clutches a skull, surrounded by the dead, as the goddesses stand as eternal witnesses. This final tableau is a stark indictment of religious complacency, state violence, and political indifference, underscoring the play’s central message: when those in power refuse to acknowledge suffering, the burden of history is left for the youngest and most vulnerable to carry.

The concept of Keibu Keioiba (Tigerman) as an absence-presence in the play is indeed a fascinating one, and it draws parallels with Ionesco’s Rhinoceros, where the titular characters symbolize conformity and societal pressures. In both works, the noticeable absence or the lurking presence of a figure can serve as a catalyst for reflection on identity, societal norms, and the human condition in the rising fascism.

In the case of Keibu Keioiba, its omnipresence might represent a cultural or existential archetype—perhaps the tension between individuality and the collective experience. This can lead to a questioning of whether we have adopted the qualities of Keibu Keioiba in our own lives, much like the characters in Rhinoceros confront the phenomenon of individuals transforming into rhinoceroses, reflecting society’s tendency toward conformity and the loss of individual thought.

Tomba’s Keibu Keioiba is not merely a retelling of folklore; it is a visceral cry against systemic failure. Through its striking imagery, minimal dialogue, and deep cultural references, the play forces its audience to confront uncomfortable truths. It demands more than passive viewing—it calls for remembrance, resistance, and reckoning.

The three-day commemorative event on the birth anniversary of Heisnam Kanhailal served as a poignant reminder of the power of art and culture to transcend societal turmoil. As participants gathered to honor the renowned Manipuri theatre director, the atmosphere was imbued with a sense of collective reflection and resilience.

Kanhailal, known for his innovative approach to theatre and storytelling, has left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of Manipur. The event featured performances, discussions, and workshops that explored his contributions and the enduring relevance of his work in today’s context. These activities not only celebrated his legacy but also sparked conversations about identity, conflict, and the role of art in healing.

In the backdrop of Manipur’s current challenges, the event became a sanctuary for dialogue and introspection. Attendees came together to share their experiences and thoughts on how the arts could act as a unifying force in a fragmented society. The themes of hope, resistance, and the search for peace resonated deeply, creating an environment where creativity and contemplation thrived.

Overall, the commemoration highlighted the importance of continuing Kanhailal’s vision and the need for artistic expression to address the complex realities of life in Manipur. It reaffirmed the idea that even amidst chaos, culture and community can provide a path toward understanding and reconciliation.

(Usham Rojio teaches at Visva-Bharati (a Central University), Santiniketan, West Bengal. He is also a theatre worker and co-author of the book Heisnam Sabitri: The Way of the Thamoi.)